|

Sunday, April 24, 2016

Kashmir: The Crown of India

Kashmiri Pandits and Music

|

Friday, April 22, 2016

Remembering the warmth of the ‘daan kuth’, the camaraderie of the ‘zoon daeb’, the coolness of the ‘kaeni’ and the joy of a door without a doorbell

BY..............

C.N. Dhar

Home

was in the change of seasons; in the rooms that don’t exist in my flat

in Delhi; in the people I have grown distant from; in some of the

rituals I no longer follow; in the nalmots (hugs, the tighter the

better) I have swapped for hellos. Home was in the study desk by the

first-floor window, from where I could see the Shankaracharya temple in

the distance.

Downstairs, Kakeni (my grandmother) would be sitting, also by the window. If she needed to call me or my sister, she just needed to put her head out and holler our names. But she had her own system—a big, thick stick with which she would tap the wooden ceiling (one tap for this, two taps for that). Downstairs, adjoining the baithak where she sat and where the family spent most of its time, was the kitchen and the daan kuth (a small partitioned area in the kitchen with wood-fired chulhas). Sharing the wall with the daan kuth was the bathroom. It had a huge copper vessel inside a concrete casing, with a tap attached to it. Come winter, the daan would be fired up every morning to cook—usually hokh syun, vegetables dried in summer—and to replenish the kangris (a pot filled with hot embers, which you hugged like a hot-water bottle underneath your pheran. Yes, that garment that can accommodate a mini-world in its circumference). The wood stoves would warm up the room, the kitchen and the copper vessel, ensuring running hot water.

Shankaracharya Temple

And then there was the zoon (moon) daeb, a sort of covered balcony, where the women would sit and watch life unfolding on the street below. It was Twitter and Instagram rolled into one; gossip travelled faster than news ever could.

The day would start with brand fash, cleaning the area in front of the main door with water at dawn, and end with syandhya choeng, the lighting of an oil lamp at dusk. The front door had no doorbell. It would be opened in the morning and closed late in the night. All through the day, the house would embrace friends, relatives, friends of friends, relatives of relatives, even strangers. And if there was a wedding in the neighbourhood and it started raining, all the rituals, guests and hangers-on would move to your kaeni and rooms. Like the other houses in the mohalla, our house had no number, but letters never got lost and guests always found their way. You just had to take the name of the head of the family and people would escort you to your destination. Everybody had time.

When you went to a wedding, you did not go empty-handed, nor did you return empty-handed—you carried a tippan (tiffin) carrier, the bigger the better, to bring back roganjosh and maetsch. If you were a child, you stood behind the groom so that when the neighbourhood ladies showered him with nabad, shireen and toffees, you could scramble to collect as many as possible. If you were a baraati, you got to savour kabargah (deep-fried lamb ribs) and modur (sweet) pulao, which were rarely served to the rest of the guests.

Kabargah, or deep-fried lamb ribs

The rest of the world was beyond the mountains. Travelling away from home meant crossing the Banihal tunnel to Jammu in winter, when schools would close for two-three months. We would come back via that same Banihal tunnel when the snow started melting. Soon spring would arrive, and tourists would start filling the shikaras, the hotels, the gardens and the Boulevard Road. They would be gone come autumn, and the same gardens and roads would be covered with chinar leaves, and then snow in winter.

It has been over two decades since my family crossed over to the other side of the mountains. The home that had been our world was looted. The house has new owners. My mother went back once; for a while, my father would go back on work, despite threats to his life. The front door of the house has been boarded for security reasons now—the same door at which my dad would stand waiting for us, the one that friends and relatives would stream through the whole day. The door at the back, which used to open on to a patch of land where we played sazloeng (hop, skip and jump) with our neighbours Daisy, Guggu and Pinki, used to have a small marble slab on the right that read “Prem Nivas”. I wonder if it’s still there.

Recently, a cousin went back to show his children their “hometown”. He said a house had come up behind ours. If I were to open the window today, I would see new faces, not the Shankaracharya beckoning in the distance. I would not be able to see our neighbour Rajlal’s daughter standing at the window of her house, calling out that there was a phone call from Delhi. We didn’t have a landline. So people would call up Rajlal’s house, telling them they would call back in 20 minutes. In the meantime, they would call us. Rajlal would always kiss me on the forehead and ask, “Which class are you in now?” Rajlal and her daughters loved the fritters mom made on Janmashtami, just as we used to wait eagerly for chai at their house on Eid. Besides hugs and kisses, we used to exchange dupattas, goodwill and a lot more. A decade ago, when my mom called her from Delhi, Rajlal had the same question, “Which class is Nipa in?” Sometimes, time stands still in your memory.

I have not gone back since 1990, though in my imagination I have travelled home several times, sat at my study desk, looked through the photo albums (which might have been thrown away as trash), rushed out of the front door to watch the Janmashtami procession, rustled through the fallen chinar leaves in the school grounds with friends, making our own music, thrown snowballs down my sister’s back and snuggled up next to Kakeni to hear the story of Sudama and Krishna that she used to narrate most evenings.

I remember the pain of trying to cope with the aloofness of a new city, which I call home now. There is no braer kakeni or zoon daeb here. I have not noticed the colours of spring or autumn here, only the harshness of summer and the briefness of winter. I cannot leave my front door open here. And though it has a doorbell, it does not ring that often.

I hope I can go home some day, and that we will be able to leave our front doors open, once again.

Downstairs, Kakeni (my grandmother) would be sitting, also by the window. If she needed to call me or my sister, she just needed to put her head out and holler our names. But she had her own system—a big, thick stick with which she would tap the wooden ceiling (one tap for this, two taps for that). Downstairs, adjoining the baithak where she sat and where the family spent most of its time, was the kitchen and the daan kuth (a small partitioned area in the kitchen with wood-fired chulhas). Sharing the wall with the daan kuth was the bathroom. It had a huge copper vessel inside a concrete casing, with a tap attached to it. Come winter, the daan would be fired up every morning to cook—usually hokh syun, vegetables dried in summer—and to replenish the kangris (a pot filled with hot embers, which you hugged like a hot-water bottle underneath your pheran. Yes, that garment that can accommodate a mini-world in its circumference). The wood stoves would warm up the room, the kitchen and the copper vessel, ensuring running hot water.

And then there was the zoon (moon) daeb, a sort of covered balcony, where the women would sit and watch life unfolding on the street below. It was Twitter and Instagram rolled into one; gossip travelled faster than news ever could.

The day would start with brand fash, cleaning the area in front of the main door with water at dawn, and end with syandhya choeng, the lighting of an oil lamp at dusk. The front door had no doorbell. It would be opened in the morning and closed late in the night. All through the day, the house would embrace friends, relatives, friends of friends, relatives of relatives, even strangers. And if there was a wedding in the neighbourhood and it started raining, all the rituals, guests and hangers-on would move to your kaeni and rooms. Like the other houses in the mohalla, our house had no number, but letters never got lost and guests always found their way. You just had to take the name of the head of the family and people would escort you to your destination. Everybody had time.

When you went to a wedding, you did not go empty-handed, nor did you return empty-handed—you carried a tippan (tiffin) carrier, the bigger the better, to bring back roganjosh and maetsch. If you were a child, you stood behind the groom so that when the neighbourhood ladies showered him with nabad, shireen and toffees, you could scramble to collect as many as possible. If you were a baraati, you got to savour kabargah (deep-fried lamb ribs) and modur (sweet) pulao, which were rarely served to the rest of the guests.

The rest of the world was beyond the mountains. Travelling away from home meant crossing the Banihal tunnel to Jammu in winter, when schools would close for two-three months. We would come back via that same Banihal tunnel when the snow started melting. Soon spring would arrive, and tourists would start filling the shikaras, the hotels, the gardens and the Boulevard Road. They would be gone come autumn, and the same gardens and roads would be covered with chinar leaves, and then snow in winter.

It has been over two decades since my family crossed over to the other side of the mountains. The home that had been our world was looted. The house has new owners. My mother went back once; for a while, my father would go back on work, despite threats to his life. The front door of the house has been boarded for security reasons now—the same door at which my dad would stand waiting for us, the one that friends and relatives would stream through the whole day. The door at the back, which used to open on to a patch of land where we played sazloeng (hop, skip and jump) with our neighbours Daisy, Guggu and Pinki, used to have a small marble slab on the right that read “Prem Nivas”. I wonder if it’s still there.

Recently, a cousin went back to show his children their “hometown”. He said a house had come up behind ours. If I were to open the window today, I would see new faces, not the Shankaracharya beckoning in the distance. I would not be able to see our neighbour Rajlal’s daughter standing at the window of her house, calling out that there was a phone call from Delhi. We didn’t have a landline. So people would call up Rajlal’s house, telling them they would call back in 20 minutes. In the meantime, they would call us. Rajlal would always kiss me on the forehead and ask, “Which class are you in now?” Rajlal and her daughters loved the fritters mom made on Janmashtami, just as we used to wait eagerly for chai at their house on Eid. Besides hugs and kisses, we used to exchange dupattas, goodwill and a lot more. A decade ago, when my mom called her from Delhi, Rajlal had the same question, “Which class is Nipa in?” Sometimes, time stands still in your memory.

I have not gone back since 1990, though in my imagination I have travelled home several times, sat at my study desk, looked through the photo albums (which might have been thrown away as trash), rushed out of the front door to watch the Janmashtami procession, rustled through the fallen chinar leaves in the school grounds with friends, making our own music, thrown snowballs down my sister’s back and snuggled up next to Kakeni to hear the story of Sudama and Krishna that she used to narrate most evenings.

I remember the pain of trying to cope with the aloofness of a new city, which I call home now. There is no braer kakeni or zoon daeb here. I have not noticed the colours of spring or autumn here, only the harshness of summer and the briefness of winter. I cannot leave my front door open here. And though it has a doorbell, it does not ring that often.

I hope I can go home some day, and that we will be able to leave our front doors open, once again.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

When women were respected and love was celebrated in Kashm

When women were respected and love was celebrated in Kashmir

Rakesh Kaul’s 'The Last Queen of Kashmir' brings to life one of the greatest queens of the land

What is faster than the mind is the very first question that challenges Princess Kota of Kashmir in The Last Queen of Kashmir during her university graduation exam?

The location was the famed Sharadapeeth University in the

pristine Kishanganga Valley of Kashmir, the time period was around the

early 14th century. Her examiners were the

illustrious Kashmiri Pandit gurus tasked with teaching, training and

graduating students from noble families, graduates who would run their

known world.

It was no easy matter to enter Sharadapeeth. The historian

Al Beruni who accompanied Mahmud of Ghazni during his conquests of India

had tried to gain entry into Kashmir to meet the gurus but was denied

his request.

Graduating into the real world, Kota quickly discovers the

power of a woman in a culture which venerated and celebrated the

feminine. Female teachers played a key role in propagating what is

referred to as Kashmir Shaivism, a universal creed which because of its

emphasis on non-duality rejects all discrimination.

In fact, the system is said to have originated from the

mouth of the Yoginis, the lady ascetics and is more appropriately

referred to as Shaktism. Sharada Devi, the tantric name for Saraswati,

the Devi of learning, is the titular deity of Kashmir. The Valley was

dotted with temples dedicated to the various representation of Shakti,

the dynamic energy within one’s self of the divine.

Kashmir was referred to as Stridesh, or the land of the

women. This feminine bias was not restricted to mystical matters only.

At a practical level it was reflected in even the smallest of

activities.

Kashmir had a fairly intriguing pre-wedding custom. At the

time that a girl and a boy would be introduced to each other, the girl

would have the ritual right to ask her future mate as to whether he was

potent and could impregnate her successfully.

The boy was supposed to reply that he had been feeding

himself nutritional supplements which were designed to maximise his

potency and virility and that he would guarantee stud performance.

Children were named the putras or putris of their mother. In

this milieu it is not surprising that woman could think big, assert

themselves with confidence and that consequently Kashmir had many role

model queens who were rulers in their own right.

In Kota’s world love was in the air. Kashmiri men and women

celebrated their love on Valentine’s Day in a joyful manner that was

liberated, healthy and emancipated. It was also very contrary to the

current puritanical notions that are imposed by moralists.

On Holi Kashmiris would celebrate Madan Trayadoshi,

Valentine’s Day with gusto. Madan, meaning he who intoxicates with love

and Trayadoshi, the 13th. It was traditionally held on the 13th of the bright half of Chaitra, (March/April) and was both a private and public event.

On the night before, the husbands would place a pitcher of

water with flowers and herbal essences before a picture of Kama painted

on cloth. Alongside Kamadeva's picture would be placed his ornaments

which are the conch and the lotus, both related to water, the symbol of

fertility and creativity.

In the morning before sunrise, the husband would wash and

scrub his wife with the fragrant water. Then he would worship her and

also worship Kama. Both husband and wife would gaily decorate themselves

and then the entire family would go to the gardens to celebrate and

enjoy a picnic.

That night wives dressed themselves in delicate, enticing

underclothes and transparent nightgowns to await their husbands and

engage in love making. Madan Trayadoshi is one of 65 festivals

that the Kashmiri Pandits celebrated, according to the Nilamat Purana,

the oldest surviving writing in Kashmir.

Most curiously there is an interesting line in the Nilamat which says, "O twice born, this (13th day) should be necessarily celebrated; the rest may or may not be celebrated."

Why? Because desire, Iccha Shakti, is considered to be the

foremost among all of the Shaktis for a

healthy existence. Beautiful Kota Rani who is desired by seven lovers

over the course of her lifetime learns a lot about what love is and

what is merely possessiveness, or far worse slavery? She opens up and

reveals her deep insight to her very first love one night, when he

rescues her from her enemy and captor.

There were no taboos in Kota’s Kashmir, the body was a

temple. Contrary to the misunderstandings and social conflicts

today, revolving around contemporary notions of feminine purity,

the Kashmirian way of life defines purity as living in the reality of

consciousness.

The menstruating woman was granted the highest honours

because she was believed to be at the height of her cyclical femininity.

In religious gatherings she would be seated to the right of the guru.

The ascetics would willingly use menstrual blood to draw

the three lines on their forehead signifying Shakti’s unfolding power

and symbolising their Shaivite afflilations. While the layman today does

not need to follow this ritual, he or she also does not need to follow

misguided notions of ritual purity based on some strand of historical

legitimacy.

In Kota’s one-word answer to the first question, that it is

desire, lay the seed of the Kashmirian pathway of life. Unlike

the limited materialistic, dualist view of the world or spiritual

frameworks that prescribe morality bordering on fanaticism, the middle

way of the Kashmirian civilisation integrated the spiritual with the

material. Follow your passion is a common refrain among the youth today.

But passion comes from the Latin word passio which means suffering.

| The Last Queen of Kashmir; HarperCollins; Rs 399 |

Kota reflects Kashmirian culture’s deep understanding when

she expands on her answer that "Desire - which is rooted in lust, the

immediate infatuation of the ten senses or ego or emotions or the

gratification of the limited mind will be incinerated like Kamadeva, the

divinity of passion. Desire, which is a genuine offering of one’s true

nature to dharma, will prevail eternally, because will is then united

with sustainability."

The fundamental question of desire, Hum ko kya chahiye, had a very different answer that everyone had complete clarity upon in Kota’s time.

The Last Queen of Kashmir is Kota’s life

story. She ruled Kashmir at a historic inflection point in its

history. It is a star-crossed love story in the midst of a historical

saga of treachery, betrayal and murder; a clash of civilisations between

universal inclusive values and one of supremacy and hegemony; of the

feminine maej or mother Kashmir versus its challenger, militant

patriarchy with its attendant misogyny; of a culture of joy and

beauty versus killjoy and nihilism.

In the telling it also reveals a model of feminine power

and leadership which was unique to Kashmir and one which was looked up

to by the rest of India.

Femininity in Kashmir was not just about equality, not just

about complementarity but about dynamic, fearless symmetry. Kota has

much to offer to the contemporary men and women of today.

Now that she has risen again she offers herself as a

measure of how much Kashmir generally and Kashmiri women specifically

have lost since her time. In the rebirth she also emerges as one of the

greatest queens of the land.

Kota Rani is described as ever captivating but never

captive. Now it is time to meet the girl who will make you kiss your

heart goodbye. Kota says, Soham I am.

When you welcome the Rani you will experience her battle cry, We were we will be. She will center you, she will empower you, she will liberate you and she will fulfill you.

Rakesh K Kaul

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

What is peanut to me may be a pot of gold to some one else. A truly humbling experience.

What is peanut

to me may be a pot of gold to some one else.

A truly humbling

experience.

Regards Srinivasan

Local driver was 28 years old chap named Jigmet. His family consist of his parents, wife and two

kid girls. This was the conversation with Jigmet, during our drives in deep Himalayan Ranges.

Prashant -: At the end of this week tourist season in Ladakh will end. Are you planning to go to

Goa, the way Nepali Workers from Hotels do?

Jigmet -: No, I am local Laddakhi, so I won't go any where in winter.

Prashant -:What work will you do in winter?

Jigmet -: Nothing, will sit up quietly at home (chuckles and winks)

Prashant -: For six months, up to next April?

Jigmet -: I have one option for working. It's to go to Siachen.

Prashant -: Siachen? What you will do there?

Jigmet -: Work as Loader for Indian Army.

Prashant -: You mean, you will join Indian Army as Jawan?

Jigmet -: No, I have crossed age limit to join Army. This is a contract job for Indian Army. With

my few friend drivers, I will travel 265 kilometers to Siachen Base camp, My medical

examination will be done there to check, if I am fit enough for this job. If I am declared fit, then

Army will issue us uniforms, shoes, warm clothing, helmets, etc, We will have to walk up

mountains for 15 days to reach Siachen. There is no motorable road to reach Siachen. We will

work there for 3 months.

Prashant -: What work will you do?

Jigmet -: It is of loader. To carry load on our back from one chowki to other in Siachen. All

supplies are airdropped there. We do the job of picking it up and carrying it in Chowki.

Prashant -: Why Army does not use Mules or vehicles for shifting of loads?

Jigmet -: Siachen is a glacier. Trucks or other vehicle will not work there. Ice scooters make too

much of sound, which will attract attention from enemy around there. Use of vehicle will result

in firing from other side. We go out in the middle of night, generally around 2 am and pick up

load silently and bring back to barracks. We can't even use a torch. Mules or horses cannot be

used because at the altitude of 18875 feet, in winter temperature of minus 50 no animal will

survive.

Prashant -: How can you lift load on your back where oxygen levels are low?

Jigmet -: We carry maximum 15 kgs at a time and we work maximum for 2 hours in a day. Rest

of the time is for recapturing.

Prashant -: That is very risky

Jigmet -: Many of my friend died there. Some of them fell in bottomless crevasses. Some got

shot down by enemy bullets. The biggest danger we have in Siachen is of frost bites.

Prashant -: This is life threatening

Jigmet -: Yes, but it's rewarding. We are paid Rs 18000/- per month. Since all expenses are taken

care of, we can save around Rs 50000/- in these three months. This money is precious for my

family, for my daughter's education and finally I have feeling that I am serving Army

The value of money and the life we have can be better understood and appreciated after reading this.

Article by :

Ravinder Tikoo

Posted by :

Vipul Koul

Edited by :

Ashok koul

Sunday, April 17, 2016

Guru Nanak Dev ji (1469 - 1539)

Guru Nanak Dev ji (1469 - 1539)

By all accounts, 1496 was the year of his enlightenment when he started on his mission. His first statement after his prophetic communion with God was "There is no Hindu, nor any Mussalman." This is an announcement of supreme significance it declared not only the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, but also his clear and primary interest not in any metaphysical doctrine but only in man and his fate. It means love your neighbour as yourself.

When Guru Nanak Dev ji were 12 years old his father gave him twenty rupees and asked him to do a business, apparently to teach him business. Guru Nanak dev ji bought food for all the money and distributed among saints, and poor. When his father asked him what happened to business? He replied that he had done a "True business" at the place where Guru Nanak dev had fed the poor, this gurdwara was made and named Sacha Sauda.

Despite the hazards of travel in those times, he performed five long tours all over the country and even outside it. He visited most of the known religious places and centres of worship. At one time he preferred to dine at the place of a low caste artisan, Bhai Lallo, instead of accepting the invitation of a high caste rich landlord, Malik Bhago, because the latter lived by exploitation of the poor and the former earned his bread by the sweat of his brow. This incident has been depicted by a symbolic representation of the reason for his preference. Sri Guru Nanak pressed in one hand the coarse loaf of bread from Lallo's hut and in the other the food from Bhago's house. Milk gushed forth from the loaf of Lallo's and blood from the delicacies of Bhago. This prescription for honest work and living and the condemnation of exploitation, coupled with the Guru's dictum that "riches cannot be gathered without sin and evil means," have, from the very beginning, continued to be the basic moral tenet with the Sikh mystics and the Sikh society.

During his tours, he visited numerous places of Hindu and Muslim worship. He explained and exposed through his preachings the incongruities and fruitlessness of ritualistic and ascetic practices. At Hardwar, when he found people throwing Ganges water towards the sun in the east as oblations to their ancestors in heaven, he started, as a measure of correction, throwing the water towards the West, in the direction of his fields in the Punjab. When ridiculed about his folly, he replied, "If Ganges water will reach your ancestors in heaven, why should the water I throw up not reach my fields in the Punjab, which are far less distant ?"

He spent twenty five years of his life preaching from place to place. Many of his hymns were composed during this period. They represent answers to the major religious and social problems of the day and cogent responses to the situations and incidents that he came across. Some of the hymns convey dialogues with Yogis in the Punjab and elsewhere. He denounced their methods of living and their religious views. During these tours he studied other religious systems like Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Islam. At the same time, he preached the doctrines of his new religion and mission at the places and centres he visited. Since his mystic system almost completely reversed the trends, principles and practices of the then prevailing religions, he criticised and rejected virtually all the old beliefs, rituals and harmful practices existing in the country. This explains the necessity of his long and arduous tours and the variety and profusion of his hymns on all the religious, social, political and theological issues, practices and institutions of his period.

Finally, on the completion of his tours, he settled as a peasant farmer at Kartarpur, a village in the Punjab. Bhai Gurdas, the scribe of Guru Granth Sahib, was a devout and close associate of the third and the three subsequent Gurus. He was born 12 years after Guru Nanak's death and joined the Sikh mission in his very boyhood. He became the chief missionary agent of the Gurus. Because of his intimate knowledge of the Sikh society and his being a near contemporary of Sri Guru Nanak, his writings are historically authentic and reliable. He writes that at Kartarpur Guru Nanak donned the robes of a peasant and continued his ministry. He organised Sikh societies at places he visited with their meeting places called Dharamsalas. A similar society was created at Kartarpur. In the morning, Japji was sung in the congregation. In the evening Sodar and Arti were recited. The Guru cultivated his lands and also continued with his mission and preachings. His followers throughout the country were known as Nanak-panthies or Sikhs. The places where Sikh congregation and religious gatherings of his followers were held were called Dharamsalas. These were also the places for feeding the poor. Eventually, every Sikh home became a Dharamsala.

One thing is very evident. Guru Nanak had a distinct sense of his prophethood and that his mission was God-ordained. During his preachings, he himself announced. "O Lallo, as the words of the Lord come to me, so do I express them." Successors of Guru Nanak have also made similar statements indicating that they were the messengers of God. So often Guru Nanak refers to God as his Enlightener and Teacher. His statements clearly show his belief that God had commanded him to preach an entirely new religion, the central idea of which was the brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God, shorn of all ritualism and priestcraft. During a dialogue with the Yogis, he stated that his mission was to help everyone. He came to be called a Guru in his lifetime. In Punjabi, the word Guru means both God and an enlightener or a prophet. During his life, his disciples were formed and came to be recognised as a separate community. He was accepted as a new religious prophet. His followers adopted a separate way of greeting each other with the words Sat Kartar (God is true). Twentyfive years of his extensive preparatory tours and preachings across the length and breadth of the country clearly show his deep conviction that the people needed a new prophetic message which God had commanded him to deliver. He chose his successor and in his own life time established him as the future Guru or enlightener of the new community. This step is of the greatest significance, showing Guru Nanak s determination and declaration that the mission which he had started and the community he had created were distinct and should be continued, promoted and developed. By the formal ceremony of appointing his successor and by giving him a new name, Angad (his part or limb), he laid down the clear principle of impersonality, unity and indivisibility of Guruship. At that time he addressed Angad by saying, Between thou and me there is now no difference. In Guru Granth Sahib there is clear acceptance and proclamation of this identity of personality in the hymns of Satta-Balwand. This unity of spiritual personality of all the Gurus has a theological and mystic implication. It is also endorsed by the fact that each of the subsequent Gurus calls himself Nanak in his hymns. Never do they call themselves by their own names as was done by other Bhagats and Illyslics. That Guru Nanak attached the highest importance to his mission is also evident from his selection of the successor by a system of test, and only when he was found perfect, was Guru Angad appointed as his successor. He was comparatively a new comer to the fold, and yet he was chosen in preference to the Guru's own son, Sri Chand, who also had the reputation of being a pious person, and Baba Budha, a devout Sikh of long standing, who during his own lifetime had the distinction of ceremonially installing all subsequent Gurus.

All these facts indicate that Guru Nanak had a clear plan and vision that his mission was to be continued as an independent and distinct spiritual system on the lines laid down by him, and that, in the context of the country, there was a clear need for the organisation of such a spiritual mission and society. In his own lifetime, he distinctly determined its direction and laid the foundations of some of the new religious institutions. In addition, he created the basis for the extension and organisation of his community and religion.

The above in brief is the story of the Guru's life. We shall now note the chief features of his work, how they arose from his message and how he proceeded to develop them during his lifetime.

(1) After his enlightenment, the first words of Guru Nanak declared the brotherhood of man. This principle formed the foundation of his new spiritual gospel. It involved a fundamental doctrinal change because moral life received the sole spiritual recognition and status. This was something entirely opposed to the religious systems in vogue in the country during the time of the Guru. All those systems were, by and large, other-worldly. As against it, the Guru by his new message brought God on earth. For the first time in the country, he made a declaration that God was deeply involved and interested in the affairs of man and the world which was real and worth living in. Having taken the first step by the proclamation of his radical message, his obvious concern was to adopt further measures to implement the same.

(2)The Guru realised that in the context and climate of the country, especially because of the then existing religious systems and the prevailing prejudices, there would be resistance to his message, which, in view of his very thesis, he wanted to convey to all. He, therefore, refused to remain at Sultanpur and preach his gospel from there. Having declared the sanctity of life, his second major step was in the planning and organisation of institutions that would spread his message. As such, his twentyfive years of extensive touring can be understood only as a major organizational step. These tours were not casual. They had a triple object. He wanted to acquaint himself with all the centres and organisations of the prevalent religious systems so as to assess the forces his mission had to contend with, and to find out the institutions that he could use in the aid of his own system. Secondly, he wanted to convey his gospel at the very centres of the old systems and point out the futile and harmful nature of their methods and practices. It is for this purpose that he visited Hardwar, Kurukshetra, Banaras, Kanshi, Maya, Ceylon, Baghdad, Mecca, etc. Simultaneously, he desired to organise all his followers and set up for them local centres for their gatherings and worship. The existence of some of these far-flung centres even up-till today is a testimony to his initiative in the Organizational and the societal field. His hymns became the sole guide and the scripture for his flock and were sung at the Dharamsalas.

(3) Guru Nanak's gospel was for all men. He proclaimed their equality in all respects. In his system, the householder's life became the primary forum of religious activity. Human life was not a burden but a privilege. His was not a concession to the laity. In fact, the normal life became the medium of spiritual training and expression. The entire discipline and institutions of the Gurus can be appreciated only if one understands that, by the very logic of Guru Nanak's system, the householder's life became essential for the seeker. On reaching Kartarpur after his tours, the Guru sent for the members of his family and lived there with them for the remaining eighteen years of his life. For the same reason his followers all over the country were not recluses. They were ordinary men, living at their own homes and pursuing their normal vocations. The Guru's system involved morning and evening prayers. Congregational gatherings of the local followers were also held at their respective Dharamsalas.

(4) After he returned to Kartarpur, Guru Nanak did not rest. He straightaway took up work as a cultivator of land, without interrupting his discourses and morning and evening prayers. It is very significant that throughout the later eighteen years of his mission he continued to work as a peasant. It was a total involvement in the moral and productive life of the community. His life was a model for others to follow. Like him all his disciples were regular workers who had not given up their normal vocations Even while he was performing the important duties of organising a new religion, he nester shirked the full-time duties of a small cultivator. By his personal example he showed that the leading of a normal man's working life was fundamental to his spiritual system Even a seemingly small departure from this basic tenet would have been misunderstood and misconstrued both by his own followers and others. In the Guru's system, idleness became a vice and engagement in productive and constructive work a virtue. It was Guru Nanak who chastised ascetics as idlers and condemned their practice of begging for food at the doors of the householders.

(5) According to the Guru, moral life was the sole medium of spiritual progress In those times, caste, religious and social distinctions, and the idea of pollution were major problems. Unfortunately, these distinctions had received religious sanction The problem of poverty and food was another moral challenge. The institution of langar had a twin purpose. As every one sat and ate at the same place and shared the same food, it cut at the root of the evil of caste, class and religious distinctions. Besides, it demolished the idea of pollution of food by the mere presence of an untouchable. Secondlys it provided food to the needy. This institution of langar and pangat was started by the Guru among all his followers wherever they had been organised. It became an integral part of the moral life of the Sikhs. Considering that a large number of his followers were of low caste and poor members of society, he, from the very start, made it clear that persons who wanted to maintain caste and class distinctions had no place in his system In fact, the twin duties of sharing one's income with the poor and doing away with social distinctions were the two obligations which every Sikh had to discharge. On this score, he left no option to anyone, since he started his mission with Mardana, a low caste Muslim, as his life long companion.

(6) The greatest departure Guru Nanak made was to prescribe for the religious man the responsibility of confronting evil and oppression. It was he who said that God destroys 'the evil doers' and 'the demonical; and that such being God s nature and will, it is man's goal to carry out that will. Since there are evil doers in life, it is the spiritual duty of the seeker and his society to resist evil and injustice. Again, it is Guru Nanak who protests and complains that Babur had been committing tyranny against the weak and the innocent. Having laid the principle and the doctrine, it was again he who proceeded to organise a society. because political and societal oppression cannot be resisted by individuals, the same can be confronted only by a committed society. It was, therefore, he who proceeded to create a society and appointed a successor with the clear instructions to develop his Panth. Again, it was Guru Nanak who emphasized that life is a game of love, and once on that path one should not shirk laying down one's life. Love of one's brother or neighbour also implies, if love is true, his or her protection from attack, injustice and tyranny. Hence, the necessity of creating a religious society that can discharge this spiritual obligation. Ihis is the rationale of Guru Nanak's system and the development of the Sikh society which he organised.

(7) The Guru expressed all his teachings in Punjabi, the spoken language of Northern India. It was a clear indication of his desire not to address the elite alone but the masses as well. It is recorded that the Sikhs had no regard for Sanskrit, which was the sole scriptural language of the Hindus. Both these facts lead to important inferences. They reiterate that the Guru's message was for all. It was not for the few who, because of their personal aptitude, should feel drawn to a life of a so-called spiritual meditation and contemplation. Nor was it an exclusive spiritual system divorced from the normal life. In addition, it stressed that the Guru's message was entirely new and was completely embodied in his hymns. His disciples used his hymns as their sole guide for all their moral, religious and spiritual purposes. I hirdly, the disregard of the Sikhs for Sanskrit strongly suggests that not only was the Guru's message independent and self-contained, without reference and resort to the Sanskrit scriptures and literature, but also that the Guru made a deliberate attempt to cut off his disciples completely from all the traditional sources and the priestly class. Otherwise, the old concepts, ritualistic practices, modes of worship and orthodox religions were bound to affect adversely the growth of his religion which had wholly a different basis and direction and demanded an entirely new approach.

The following hymn from Guru Nanak and the subsequent one from Sankara are contrast in their approach to the world.

"the sun and moon, O Lord, are Thy lamps; the firmament Thy salver; the orbs of the stars the pearls encased in it.

The perfume of the sandal is Thine incense, the wind is Thy fan, all the forests are Thy flowers, O Lord of light.

What worship is this, O Thou destroyer of birth ? Unbeaten strains of ecstasy are the trumpets of Thy worship.

Thou has a thousand eyes and yet not one eye; Thou host a thousand forms and yet not one form;

Thou hast a thousand stainless feet and yet not one foot; Thou hast a thousand organs of smell and yet not one organ. I am fascinated by this play of 'l hine.

The light which is in everything is Chine, O Lord of light.

From its brilliancy everything is illuminated;

By the Guru's teaching the light becometh manifest.

What pleaseth Thee is the real worship.

O God, my mind is fascinated with Thy lotus feet as the bumble-bee with the flower; night and day I thirst for them.

Give the water of Thy favour to the Sarang (bird) Nanak, so that he may dwell in Thy Name."3

Sankara writes: "I am not a combination of the five perishable elements I arn neither body, the senses, nor what is in the body (antar-anga: i e., the mind). I am not the ego-function: I am not the group of the vital breathforces; I am not intuitive intelligence (buddhi). Far from wife and son am 1, far from land and wealth and other notions of that kind. I am the Witness, the Eternal, the Inner Self, the Blissful One (sivoham; suggesting also, 'I am Siva')."

"Owing to ignorance of the rope the rope appears to be a snake; owing to ignorance of the Self the transient state arises of the individualized, limited, phenomenal aspect of the Self. The rope becomes a rope when the false impression disappears because of the statement of some credible person; because of the statement of my teacher I am not an individual life-monad (yivo-naham), I am the Blissful One (sivo-ham )."

"I am not the born; how can there be either birth or death for me ?"

"I am not the vital air; how can there be either hunger or thirst for me ?"

"I am not the mind, the organ of thought and feeling; how can there be either sorrow or delusion for me ?"

"I am not the doer; how can there be either bondage or release for me ?"

"I am neither male nor female, nor am I sexless. I am the Peaceful One, whose form is self-effulgent, powerful radiance. I am neither a child, a young man, nor an ancient; nor am I of any caste. I do not belong to one of the four lifestages. I am the Blessed-Peaceful One, who is the only Cause of the origin and dissolution of the world."4

While Guru Nanak is bewitched by the beauty of His creation and sees in the panorama of nature a lovely scene of the worshipful adoration of the Lord, Sankara in his hymn rejects the reality of the world and treats himself as the Sole Reality. Zimmer feels that "Such holy megalomania goes past the bounds of sense. With Sankara, the grandeur of the supreme human experience becomes intellectualized and reveals its inhuman sterility."5

No wonder that Guru Nanak found the traditional religions and concepts as of no use for his purpose. He calculatedly tried to wean away his people from them. For Guru Nanak, religion did not consist in a 'patched coat or besmearing oneself with ashes"6 but in treating all as equals. For him the service of man is supreme and that alone wins a place in God's heart.

By this time it should be easy to discern that all the eight features of the Guru's system are integrally connected. In fact, one flows from the other and all follow from the basic tenet of his spiritual system, viz., the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. For Guru Nanak, life and human beings became the sole field of his work. Thus arose the spiritual necessity of a normal life and work and the identity of moral and spiritual functioning and growth.

Having accepted the primacy of moral life and its spiritual validity, the Guru proceeded to identify the chief moral problems of his time. These were caste and class distinctions, the institutions, of property and wealth, and poverty and scarcity of food. Immoral institutions could be substituted and replaced only by the setting up of rival institutions. Guru Nanak believed that while it is essential to elevate man internally, it is equally necessary to uplift the fallen and the downtrodden in actual life. Because, the ultimate test of one's spiritual progress is the kind of moral life one leads in the social field. The Guru not only accepted the necessity of affecting change in the environment, but also endeavoured to build new institutions. We shall find that these eight basic principles of the spirituo-moral life enunciated by Guru Nanak, were strictly carried out by his successors. As envisaged by the first prophet, his successors further extended the structure and organised the institutions of which the foundations had been laid by Guru Nanak. Though we shall consider these points while dealing with the lives of the other nine Gurus, some of them need to be mentioned here.

The primacy of the householder's life was maintained. Everyone of the Gurus, excepting Guru Harkishan who died at an early age, was a married person who maintained a family. When Guru Nanak, sent Guru Angad from Kartarpur to Khadur Sahib to start his mission there, he advised him to send for the members of his family and live a normal life. According to Bhalla,8 when Guru Nanak went to visit Guru Angad at Khadur Sahib, he found him living a life of withdrawal and meditation. Guru Nanak directed him to be active as he had to fulfill his mission and organise a community inspired by his religious principles.

Work in life, both for earning the livelihood and serving the common good, continued to be the fundamental tenet of Sikhism. There is a clear record that everyone upto the Fifth Guru (and probably subsequent Gurus too) earned his livelihood by a separate vocation and contributed his surplus to the institution of langar Each Sikh was made to accept his social responsibility. So much so that Guru Angad and finally Guru Amar Das clearly ordered that Udasis, persons living a celibate and ascetic life without any productive vocation, should remain excluded from the Sikh fold. As against it, any worker or a householder without distinction of class or caste could become a Sikh. This indicates how these two principles were deemed fundamental to the mystic system of Guru Nanak. It was defined and laid down that in Sikhism a normal productive and moral life could alone be the basis of spiritual progress. Here, by the very rationale of the mystic path, no one who was not following a normal life could be fruitfully included.

The organization of moral life and institutions, of which the foundations had been laid by Guru Nanak, came to be the chief concern of the other Gurus. We refer to the sociopolitical martyrdoms of two of the Gurus and the organisation of the military struggle by the Sixth Guru and his successors. Here it would be pertinent to mention Bhai Gurdas's narration of Guru Nanak's encounter and dialogue with the Nath Yogis who were living an ascetic life of retreat in the remote hills. They asked Guru Nanak how the world below in the plains was faring. ' How could it be well", replied Guru Nanak, "when the so- called pious men had resorted to the seclusion of the hills ?" The Naths commented that it was incongruous and self-contradictory for Guru Nanak to be a householder and also pretend to lead a spiritual life. That, they said, was like putting acid in milk and thereby destroying its purity. The Guru replied emphatically that the Naths were ignorant of even the basic elements of spiritual life.9 This authentic record of the dialouge reveals the then prevailing religious thought in the country. It points to the clear and deliberate break the Guru made from the traditional system.

While Guru Nanak was catholic in his criticism of other religions, he was unsparing where he felt it necessary to clarify an issue or to keep his flock away from a wrong practice or prejudice. He categorically attacked all the evil institutions of his time including oppression and barbarity in the political field, corruption among the officialss and hypocrisy and greed in the priestly class. He deprecated the degrading practices of inequality in the social field. He criticised and repudiated the scriptures that sanctioned such practices. After having denounced all of them, he took tangible steps to create a society that accepted the religious responsibility of eliminating these evils from the new institutions created by him and of attacking the evil practices and institutions in the Social and political fields. T his was a fundamental institutional change with the largest dimensions and implications for the future of the community and the country. The very fact that originally poorer classes were attracted to the Gurus, fold shows that they found there a society and a place where they could breathe freely and live with a sense of equality and dignity.

Dr H.R. Gupta, the well-known historian, writes, "Nanak's religion consisted in the love of God, love of man and love of godly living. His religion was above the limits of caste, creed and country. He gave his love to all, Hindus, Muslims, Indians and foreigners alike. His religion was a people's movement based on modern conceptions of secularism and socialism, a common brotherhood of all human beings. Like Rousseau, Nanak felt 250 years earlier that it was the common people who made up the human race Ihey had always toiled and tussled for princes, priests and politicians. What did not concern the common people was hardly worth considering. Nanak's work to begin with assumed the form of an agrarian movement. His teachings were purely in Puniabi language mostly spoken by cultivators. Obey appealed to the downtrodden and the oppressed peasants and petty traders as they were ground down between the two mill stones of Government tyranny and the new Muslims' brutality. Nanak's faith was simple and sublime. It was the life lived. His religion was not a system of philosophy like Hinduism. It was a discipline, a way of life, a force, which connected one Sikh with another as well as with the Guru."'� "In Nanak s time Indian society was based on caste and was divided into countless watertight Compartments. Men were considered high and low on account of their birth and not according to their deeds. Equality of human beings was a dream. There was no spirit of national unity except feelings of community fellowship. In Nanak's views men's love of God was the criterion to judge whether a person was good or bad, high or low. As the caste system was not based on divine love, he condemned it. Nanak aimed at creating a casteless and classless society similar to the modern type of socialist society in which all were equal and where one member did not exploit the other. Nanak insisted that every Sikh house should serve as a place of love and devotion, a true guest house (Sach dharamshala). Every Sikh was enjoined to welcome a traveller or a needy person and to share his meals and other comforts with him. "Guru Nanak aimed at uplifting the individual as well as building a nation."

Considering the religious conditions and the philosophies of the time and the social and political milieu in which Guru Nanak was born, the new spirituo- moral thesis he introduced and the changes he brought about in the social and spiritual field were indeed radical and revolutionary. Earlier, release from the bondage of the world was sought as the goal. The householder's life was considered an impediment and an entanglement to be avoided by seclusion, monasticism, celibacy, sanyasa or vanpraslha. In contrast, in the Guru's system the world became the arena of spiritual endeavour. A normal life and moral and righteous deeds became the fundamental means of spiritual progress, since these alone were approved by God. Man was free to choose between the good and the bad and shape his own future by choosing virtue and fighting evil. All this gave "new hope, new faith, new life and new expectations to the depressed, dejected and downcast people of Punjab."

Guru Nanak's religious concepts and system were entirely opposed to those of the traditional religions in the country. His views were different even from those of the saints of the Radical Bhakti movement. From the very beginning of his mission, he started implementing his doctrines and creating institutions for their practice and development. In his time the religious energy and zeal were flowing away from the empirical world into the desert of otherworldliness, asceticism and renunciation. It was Guru Nanak's mission and achievement not only to dam that Amazon of moral and spiritual energy but also to divert it into the world so as to enrich the moral, social the political life of man. We wonder if, in the context of his times, anything could be more astounding and miraculous. The task was undertaken with a faith, confidence and determination which could only be prophetic.

It is indeed the emphatic manifestation of his spiritual system into the moral formations and institutions that created a casteless society of people who mixed freely, worked and earned righteously, contributed some of their income to the common causes and the langar. It was this community, with all kinds of its shackles broken and a new freedom gained, that bound its members with a new sense of cohesion, enabling it to rise triumphant even though subjected to the severest of political and military persecutions.

The life of Guru Nanak shows that the only interpretation of his thesis and doctrines could be the one which we have accepted. He expressed his doctrines through the medium of activities. He himself laid the firm foundations of institutions and trends which flowered and fructified later on. As we do not find a trace of those ideas and institutions in the religious milieu of his time or the religious history of the country, the entirely original and new character of his spiritual system could have only been mystically and prophetically inspired.

Apart from the continuation, consolidation and expansion of Guru Nanak's mission, the account that follows seeks to present the major contributions made by the remaining Gurus.

POSTED BY : VIPUL KOUL

EDITED BY : ASHOK KOUL

Saturday, April 16, 2016

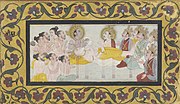

Bhishma

In the epic Mahabharata, Devavrata also known as Gangaputra and Bhishma (Sanskrit: भीष्म) was well known for his celibate pledge, the eighth son of Kuru King Shantanu, who was blessed with wish-long life and had sworn to serve the ruling Kuru king and grandfather of both the Pandavas and the Kauravas. He was an unparalleled archer and warrior of his time. He also handed down the Vishnu Sahasranama to Yudhishthira when he was on his death bed (of arrows) in the battlefield of Kurukshetra.He also belonged to the Sankriti Gotra.

The legend behind Bhishma's birth is as follows — once the eight Vasus ("Ashtavasus") visited Vashishta's ashram accompanied by their wives. One of the wives took a fancy to Kamadhenu,

Vashishta's wish-bearing cow and asked her husband Prabhasa to steal it

from Vashishta. Prabhasa then stole the cow with the help of the others

who were all consequently cursed by Vashishta to be born in the world

of humans. Upon the Vasus appealing to Vashishta's mercy, the seven

Vasus who had assisted in stealing Kamadhenu had their curse mitigated

such that they would be liberated from their human birth as soon as they

were born; however, Prabhasa being protagonist of the theft, was cursed

to endure a longer life on the earth. The curse, however is softened to

the extent that he would be one of the most illustrious men of his

time. It was this Prabhasa who took birth as Bhishma.

After Devavrata was born, his mother Ganga took him to different realms, where he was brought up and trained by many eminent sages(Mahabharata Shanti Parva, section 38).

Bhishma means He of the terrible oath, referring to his vow of lifelong celibacy. Originally named Devavratha, he became known as Bhishma after he took the bhishama pratigya ('terrible oath') — the vow of lifelong celibacy and of service to whomever sat on the throne of his father (the throne of Hastinapur). He took this oath so that his father, Shantanu could marry a fisherwoman Satyavati

— Satyavati's father had refused to give his daughter's hand to

Shantanu on the grounds that his daughter's children would never be

rulers. This made Shantanu despondent, and upon discovering the reason

for his father's despondency,[2]

Devavratha sought out the girl's father and promised him that he would

never stake a claim to the throne, implying that the child born to

Shantanu and Satyavati would become the ruler after Shantanu. At this,

Satyavati's father retorted that even if Devavratha gave up his claim to

the throne, his (Devavratha's) children would still claim the throne.

Devavratha then took the vow of lifelong celibacy, thus sacrificing his

'crown-prince' title and denying himself the pleasures of conjugal love.

This gave him immediate recognition among the gods. His father granted

him the boon of Ichcha Mrityu (control over his own death — he

could choose the time of his death, making him immortal till his chosen

time of death, instead of completely immortal which would have been an

even more severe curse and cause of suffering).

Criticism of King Shantanu from his subjects as to why he removed Bhishma from the title of the crown prince, as he was so capable, abounded. There was worry about the nobility of Shantanu's unborn children, now promised the throne. Hearing this, Bhishma said it was his decision and his father should not be blamed as Shantanu had never promised anything to Satyavati's father. The prime minister then asked who would be held responsible if the future crown prince isn't capable enough. Bhishma then took another vow that he would always see his father's image in whomever sat on the King's throne, and would thus serve him faithfully.

Years later, in the process of finding a bride for his half-brother, the young king Vichitravirya, Bhishma abducted princesses Amba, Ambika and Ambalika of Kashi (Varanasi) from the assemblage of suitors at their swayamvara. Salwa, the ruler of Saubala, and Amba (the eldest princess) were in love; Salwa attempted to stop the abduction but was soundly beaten. Upon reaching Hastinapura, Amba confided in Bhishma that she wished to wed Salwa. Bhishma then sent her back to Salwa, who, bitter from his humiliating defeat at Bhishma's hands, turned her down. Disgraced, Amba approached Bhishma for marriage. He refused her, citing his oath. Enraged beyond measure, Amba vowed to avenge herself against Bhishma even if it meant being reborn over and over again.

Amba sought refuge with Parasurama, who ordered Bhishma to marry Amba, telling Bhishma it was his duty.

Bhishma politely refused saying that he was ready to give up his life

at the command of his teacher but not the promise that he had made. Upon

the refusal, Parasurama called him for a fight at Kurukshetra.

At the battlegrounds, while Bhishma was on a chariot, Parasurama was on

foot. Bhishma requested Parasurama to also take a chariot and armor so

that Bhishma would not have an unfair advantage. Parasurama blessed

Bhishma with the power of divine vision and asked him to look again.

When Bhishma looked at his guru with the divine eyesight, he saw the Earth as Parasurama's chariot, the four Vedas as the horses, the Upanishads as the reins, Vayu (wind) as the Charioteer and the Vedic goddesses Gayatri, Savitri, and Saraswati

as his armor. Bhishma got down from the chariot and sought the

blessings of Parashurama to protect his dharma, along with permission to

battle against his teacher. Pleased, Parashurama blessed him and

advised him to protect his vow as Parasurama himself had to fight to

uphold his word as given to Amba. They fought for 23 days without

conclusion, each too powerful to defeat the other.

In one version of the epic, on the 23rd day of battle, Bhishma attempted to use the Prashwapastra against Parashurama. Learned in his previous birth as Prabhasa (one of Ashta Vasus), this weapon was not known to Parasurama and would put the afflicted to sleep in the battlefield. This would have given Bhishma the victory. Before he could release it, however, a voice from the sky warned him that "if he uses this weapon it would be a great insult towards his Guru." Pitrs then appeared and obstructed the chariot of Parashurama, forbidding him from fighting any longer. At the behest of the divine sage Narada and the gods, Parashurama ended the conflict and the battle was declared a draw by Gods.[4]

Parashurama narrated the events to Amba and told her to seek Bhishma's protection. However, Amba refused to listen to Parashurama's advice and left angrily declaring that she would achieve her objective by asceticism. Her predicament unchanged, did severe penance to please Lord Shiva. Lord Shiva assured her that she would be born as a man named (Shikhandi) in her next birth (and still she would recall her past) and could be instrumental in Bhishma's death, thus satisfying her vow.Vichitravirya fell ill and died without siring any children. Bhishma's step mother, Satyavati, begged him to sire children on Vichitravirya's wives, but Bhishma could not break his vow of lifelong celibacy. Satyavati revealed to Bhishma that before she married Shantanu, she secretly had a son with the Sage Parashara. Satyavati summoned her son, the Sage Vyasa and he sired Dhritarashtra and Pandu on Ambika and Ambalika. Bhishma, despite being a renunciate, was forced to look after the Pandavas and the Kauravas, as Pandu died an untimely death and Dhritarashtra was blind. Bhishma appointed Dronacharya, who was another former disciple of Parashurama, as the martial instructor for the Kauravas and the Pandavas. Despite his efforts, Bhishma was unable to resolve the childhood rivalry between the Pandavas and the Kauravas, which later resulted in a blood feud and a devastating war. Throughout his life, Bhishma tried to convince Duryodhana to give up this hatred but failed. Bhishma guided the Pandavas, but was highly criticized for remaining silent and motionless during the controversial game of dice and did nothing to help when princess Draupadi was being humiliated and abused in the royal court.

In the great battle at Kurukshetra, Bhishma was the supreme commander of the Kaurava forces for ten days. He fought reluctantly on the side of the Kauravas.

Bhishma was one of the most powerful warrior of his time and in

history. He acquired his prowess and invincibility from being the son of

the sacred Ganga and by being a student of renowned Gurus.

Despite being about five generations old, Bhishma was too powerful to

be defeated by any warrior alive at that time. Every day, he slew at

least 10,000 soldiers and about a 1,000 chariot warriors. At the

beginning of the war, Bhishma vowed not to kill any of the Pandavas, as

he loved them, being their grandsire. Duryodhan often confronted Bhishma

alleging that he was not actually fighting for the Kaurava camp as he

wouldn't kill any Pandava but would let them attack the Kaurava

brothers.

Duryodhana approached Bhishma one night and accused him of not fighting the battle to his full strength because of his affection for the Pandavas.The angry Bhishma took a vow that either he will kill Arjuna or will make Lord Krishna break his promise of not picking up any weapons during the war. On the next day there was an intense battle between Bhishma and Arjuna. Although Arjuna was very powerful, he was no match for Bhishma. Bhishma soon shot arrows which cut Arjuna's armour and then also his Gandiva bow`s thread. Arjuna was helpless before the wrath of the grandsire. As Bhishma was about to kill Arjuna with his arrows, Sri Krishna who took vow of not raising a weapon in the war, lifted a chariot wheel and threatened Bhishma. Arjuna stopped Lord Krishna. Arjuna convinced Krishna to return to the chariot and put down the wheel, promising to redouble his determination in the fight. Thus Bhishma fulfilled his vow.

The war was thus locked in a stalemate. As the Pandavas mulled over this situation, Krishna advised them to visit Bhishma himself and request him to suggest a way out of this stalemate. Bhishma knew loved the Pandavas and knew that he stood as the greatest obstacle in their path to victory so when they visited Bhishma, he gave them a hint as to how they could defeat him. He told them that if faced by one who had once been of the opposite gender, he would lay down his arms and fight no longer.

Later the Krishna told Arjuna how he could bring down the old grandsire, through the help of Sikhandhi. The Pandavas were initially not agreeable to such a ploy, as by using such cheap tactics they would not be following the path of Dharma, but Krishna suggested a clever alternative. And thus, on the next day, the tenth day of battle Shikhandi accompanied Arjuna on the latter's chariot and they faced Bhishma who put his bow and arrows down. He was then felled in battle by Arjuna, pierced by innumerable arrows. Using Sikhandhi as a shield, Arjuna shot arrows at Bhishma, piercing his entire body. Thus, as was preordained (Mahadeva's boon to Amba that she would be the cause of Bhishma's death) Shikhandi, that is, Amba reincarnated was the cause of Bhishma's fall. As Bhishma fell, his whole body was held above the ground by the shafts of Arjuna's arrows which protruded from his back, and through his arms and legs. Seeing Bhishma lying on such a bed of arrows humbled even the gods who watched from the heavens in reverence. They silently blessed the mighty warrior. When the young princes of both armies gathered around him, inquiring if there was anything they could do, he told them that while his body lay on the bed of arrows above the ground, his head hung unsupported. Hearing this, many of the princes, both Kaurava and the Pandava alike brought him pillows of silk and velvet, but he refused them. He asked Arjuna to give him a pillow fit for a warrior. Arjuna then removed three arrows from his quiver and placed them underneath Bhishma's head, the pointed arrow tips facing upwards. To quench the war veteran's thirst, Arjuna shot an arrow into the earth, and a jet stream of water rose up and into Bhishma's mouth. It is said that Ganga herself rose to quench her son's thirst.

Finally Bhishma gave up the fight, focusing his life force and

breath, sealing the wounds, and waiting for the auspicious moment to

give up his body. Bhishma witnessed the entire destruction of his

lineage while awaiting his death in the bed of arrows.

Bhishma is often considered as a great example of devotion and sacrifice. His name itself is an honour to him, Bhishma which means severe because he took a severe vow to remain celibate for life and Pitamah which means Grandfather which combined means Great Grandsire. Bhishma was one of the greatest Bramhacharis of all time. Accumulation of Ojas due to his Bramhacharyam made him the strongest warrior of the era. He had stature and personality that in those times were fit for kings. He was a true Kshatriya as well as a disciplined ascetic - a rare combination. Like a true Kshatriya, he never unnecessarily exhibited passion and anger. A symbol of truth and duty, the benevolent Bhishma was in all senses a true human . It is unfortunate that a person as noble as Bhishma saw a life full of loneliness, frustration and sadness. But that was how Vashishta's curse was supposed to unfold. Bhishma's human birth was destined to be marked with suffering, and that was how his life transpired right till the last moment; even his death was very painful . But the strong as steel character which he possessed ensured that he never shied away from his duty, and never stopped loving those dear to him.

Despite being an erudite scholar, a disciplined ascetic and a powerful warrior, Bhishma wasn't without his flaws. He rashly kidnapped the three princesses of Kashi against their will, on behalf of his half brother. Bhishma failed to correct Duryodhana from his wicked ways, and he also failed to save Draupadi from being disrobed in public.

Bhishma was an invincible warrior. He was also a highly skilled in political science. He had all the qualities and abilities for an excellent king. His goodness and sacrifice made him one of the greatest devotees of Lord Krishna himself. He tried his best to bring reconciliation between the Pandavas and Kauravas to prevent the war. Even in the Kurukshetra war, while he was the general, he tried his best to keep the war low key by minimizing confrontation between the two camps. Even as he fell he tried to use the opportunity to persuade both camps to put an end to the war.

After the war, while on his deathbed he gave deep and meaningful instructions to Yudhishthira on statesmanship and the duties of a king. Bheeshma always gave priority to Dharma. He always walked in path of Dharma, even though his circumstances because of his promise, he was supposed to forcefully follow the orders of his king Dhritharashtra, which were mostly Adharma, he was totally upset. In between the Kurukshetra War Lord Krishna advised Bheeshma that, when duties are to be followed you have to follow them without looking for the promises, if those promises are making path for sadness to the society it has to be broken at that point itself and should be given priority to the moral duty only. Bheeshma was a complete human. a complete warrior and a complete teacher(aacharya), hence he was known as Bheeshmacharya.

Shantanu stops Ganga from drowning their eighth child, who later was known as Bhishma.

After Devavrata was born, his mother Ganga took him to different realms, where he was brought up and trained by many eminent sages(Mahabharata Shanti Parva, section 38).

- Brihaspati: The son of Angiras and the preceptor of the Devas taught Devavrata the duties of kings (Dandaneeti), or political science and other Shastras.

- Shukracharya: The son of Bhrigu and the preceptor of the Asuras also taught Devavrata in political science and other branches of knowledge.

- Vashishtha, the Brahmarshi and Chyavana, the son of Bhrigu taught the Vedangas and other holy scriptures to Devavrata who mastered the Vedas.

- Sanatkumara: The eldest son of Lord Brahma, taught Devavrata the mental and spiritual sciences, also called the Ânvîkshîkî.

- Markandeya: The immortal son of Mrikandu of Bhrigu's race who acquired everlasting youth from Lord Shiva taught Devavrata in the duties of Brahmanas.

- Parashurama: The son of Jamadagni of Bhrigu's race. Parashurama trained Bhishma in warfare.

- Indra: It is mentioned by Vyasa that Bhishma also acquired celestial weapons from Indra.

Bhishma taking his bhishama pratigya

Criticism of King Shantanu from his subjects as to why he removed Bhishma from the title of the crown prince, as he was so capable, abounded. There was worry about the nobility of Shantanu's unborn children, now promised the throne. Hearing this, Bhishma said it was his decision and his father should not be blamed as Shantanu had never promised anything to Satyavati's father. The prime minister then asked who would be held responsible if the future crown prince isn't capable enough. Bhishma then took another vow that he would always see his father's image in whomever sat on the King's throne, and would thus serve him faithfully.

Years later, in the process of finding a bride for his half-brother, the young king Vichitravirya, Bhishma abducted princesses Amba, Ambika and Ambalika of Kashi (Varanasi) from the assemblage of suitors at their swayamvara. Salwa, the ruler of Saubala, and Amba (the eldest princess) were in love; Salwa attempted to stop the abduction but was soundly beaten. Upon reaching Hastinapura, Amba confided in Bhishma that she wished to wed Salwa. Bhishma then sent her back to Salwa, who, bitter from his humiliating defeat at Bhishma's hands, turned her down. Disgraced, Amba approached Bhishma for marriage. He refused her, citing his oath. Enraged beyond measure, Amba vowed to avenge herself against Bhishma even if it meant being reborn over and over again.

Bhishma abducting princesses Amba, Ambika and Ambalika from the assemblage of suitors at their swayamvara.

In one version of the epic, on the 23rd day of battle, Bhishma attempted to use the Prashwapastra against Parashurama. Learned in his previous birth as Prabhasa (one of Ashta Vasus), this weapon was not known to Parasurama and would put the afflicted to sleep in the battlefield. This would have given Bhishma the victory. Before he could release it, however, a voice from the sky warned him that "if he uses this weapon it would be a great insult towards his Guru." Pitrs then appeared and obstructed the chariot of Parashurama, forbidding him from fighting any longer. At the behest of the divine sage Narada and the gods, Parashurama ended the conflict and the battle was declared a draw by Gods.[4]

Parashurama narrated the events to Amba and told her to seek Bhishma's protection. However, Amba refused to listen to Parashurama's advice and left angrily declaring that she would achieve her objective by asceticism. Her predicament unchanged, did severe penance to please Lord Shiva. Lord Shiva assured her that she would be born as a man named (Shikhandi) in her next birth (and still she would recall her past) and could be instrumental in Bhishma's death, thus satisfying her vow.Vichitravirya fell ill and died without siring any children. Bhishma's step mother, Satyavati, begged him to sire children on Vichitravirya's wives, but Bhishma could not break his vow of lifelong celibacy. Satyavati revealed to Bhishma that before she married Shantanu, she secretly had a son with the Sage Parashara. Satyavati summoned her son, the Sage Vyasa and he sired Dhritarashtra and Pandu on Ambika and Ambalika. Bhishma, despite being a renunciate, was forced to look after the Pandavas and the Kauravas, as Pandu died an untimely death and Dhritarashtra was blind. Bhishma appointed Dronacharya, who was another former disciple of Parashurama, as the martial instructor for the Kauravas and the Pandavas. Despite his efforts, Bhishma was unable to resolve the childhood rivalry between the Pandavas and the Kauravas, which later resulted in a blood feud and a devastating war. Throughout his life, Bhishma tried to convince Duryodhana to give up this hatred but failed. Bhishma guided the Pandavas, but was highly criticized for remaining silent and motionless during the controversial game of dice and did nothing to help when princess Draupadi was being humiliated and abused in the royal court.

Arjuna fight Bhishma

Duryodhana approached Bhishma one night and accused him of not fighting the battle to his full strength because of his affection for the Pandavas.The angry Bhishma took a vow that either he will kill Arjuna or will make Lord Krishna break his promise of not picking up any weapons during the war. On the next day there was an intense battle between Bhishma and Arjuna. Although Arjuna was very powerful, he was no match for Bhishma. Bhishma soon shot arrows which cut Arjuna's armour and then also his Gandiva bow`s thread. Arjuna was helpless before the wrath of the grandsire. As Bhishma was about to kill Arjuna with his arrows, Sri Krishna who took vow of not raising a weapon in the war, lifted a chariot wheel and threatened Bhishma. Arjuna stopped Lord Krishna. Arjuna convinced Krishna to return to the chariot and put down the wheel, promising to redouble his determination in the fight. Thus Bhishma fulfilled his vow.

The war was thus locked in a stalemate. As the Pandavas mulled over this situation, Krishna advised them to visit Bhishma himself and request him to suggest a way out of this stalemate. Bhishma knew loved the Pandavas and knew that he stood as the greatest obstacle in their path to victory so when they visited Bhishma, he gave them a hint as to how they could defeat him. He told them that if faced by one who had once been of the opposite gender, he would lay down his arms and fight no longer.