| Narasimha | |

|---|---|

| God of Protection | |

Vishnu as Narasimha after slaying Hiranyakashipu, Group of Monuments at Badami.

|

|

| Affiliation | Lion headed man, fourth Avatar of Vishnu[1] |

| Weapon | Chakra, mace, Nails and Jaws |

| Festivals | Narasimha Jayanti |

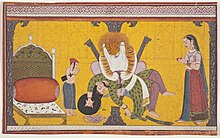

Narasimha iconography shows him with a human torso and lower body, with a lion face and claws, typically with a demon Hiranyakashipu in his lap whom he is in the process of killing. The demon is powerful brother of evil Hiranyaksha who had been previously killed by Vishnu, who hated Vishnu for killing his brother.[3] Hiranyakashipu gains special powers by which he could not be killed during the day or night, inside or outside, by god, demon, man or animal.[4] Coronated with his new powers, Hiranyakashipu creates chaos, persecutes all devotees of Vishnu including his own son.[1][4][5] Vishnu understands the demon's power, then creatively adapts into a mixed avatar that is neither man nor animal and kills the demon at the junction of day and night, inside and outside.[1] Narasimha is known primarily as the 'Great Protector' who specifically defends and protects his devotees from evil.[6] The most popular Narasimha mythology is the legend that protects his devotee Prahlada, and creatively destroys Prahlada's demonic father and tyrant Hiranyakashipu.[4][7]

Narasimha legends are revered in Vaishnavism, but he is a popular deity beyond the Vaishnava tradition such as in Shaivism.[8] He is celebrated in many regional Hindu temples, texts, performance arts and festivals such as Holika prior to the Hindu spring festival of colors called Holi.[4][9] The oldest known artwork of Narasimha has been found at several sites across Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh, such as at the Mathura archaeological site. These have been variously dated between 2nd and 4th-century CE.[10]

The word Narasimha consists of two words "nara" which means man, and "simha" which means lion. Together the term means "man-lion", referring to a mixed creature avatar of Vishnu.[1][4]

He is known as Narasingh, Narasingha, Narasimba and Narasinghar in derivative languages. His other names are Agnilochana (अग्निलोचन) - the one who has fiery eyes, Bhairavadambara (भैरवडम्बर) - the one who causes terror by roaring, Karala (कराल) - the one who has a wide mouth and projecting teeth, Hiranyakashipudvamsa (हिरण्यकशिपुध्वंस) - the one who killed Hiranyakashipu, Nakhastra (नखास्त्र) - the one for whom nails are his weapons, Sinhavadana (सिंहवदन) - the whose face is of lion and Mrigendra (मृगेन्द्र) - king of animals or lion

Narasimha is also found in the Mahābhārata (3.272.56-60) and is the focus of Nrisimha Tapaniya Upanishad.[20][21]

Mythologies

Prahlāda legend

Viṣṇu as Narasiṃha kills Hiraṇyakaśipu, stone sculpture from the Hoysaleswara Temple in Halebidu, Karnataka

Narasiṃha kills Hiraṇyakaśipu, as Prahlāda and Lakshmi devi bow before Lord Narasiṃha

In an alternate version of the story, Prahlāda answers,

He is in pillars, and he is in the smallest twig.Hiraṇyakaśipu, unable to control his anger, smashes the pillar with his mace, and following a tumultuous sound, Viṣṇu in the form of Narasiṃha appears from it and moves to attack Hiraṇyakaśipu in defense of Prahlāda. In order to kill Hiraṇyakaśipu and not upset the boon given by Brahma, the form of Narasiṃha is chosen. Hiraṇyakaśipu can not be killed by human, deva or animal. Narasiṃha is neither one of these as he is a form of Viṣṇu incarnate as a part-human, part-animal. He comes upon Hiraṇyakaśipu at twilight (when it is neither day nor night) on the threshold of a courtyard (neither indoors nor out), and puts the demon on his thighs (neither earth nor space). Using his sharp fingernails (neither animate nor inanimate) as weapons, he disembowels and kills the demon king.[citation needed]

Kūrma Purāṇa describes the preceding battle between the Puruṣa and demonic forces in which he escapes a powerful weapon called Paśupāta. According to Soifer, it describes how Prahlāda's brothers headed by Anuhrāda and thousands of other demons "were led to the valley of death (yamalayam) by the lion produced from the body of man-lion".[22] The same episode occurs in the Matsya Purāṇa 179, several chapters after its version of the Narasiṃha advent.[9]

Iconography

Narasimha is always shown with a lion face with clawed fingers fused with a human body. Sometimes he is coming out of a pillar signifying that he is everywhere, in everything, in everyone. Some temples such as at Ahobilam, Andhra Pradesh, the iconography is more extensive, and includes nine other icons of Narasimha:[4]- Prahladavarada: blessing Prahlada

- Yogānanda-narasiṃha: serene, peaceful Narasimha teaching yoga

- Guha-narasiṃha: concealed Narasimha

- Krodha-narasiṃha: angry Narasimha

- Vira-narasimha: warrior Narasimha

- Malola-narasiṃha: with Lakshmi his wife

- Jvala-narasiṃha: Narasimha emitting flames of wrath

- Sarvatomukha-narasimha: many faced Narasimha

- Bhishana-narasimha: ferocious Narasimha

- Bhadra-narasimha: another fierce aspect of Narasimha

- Mrityormrityu-narasimha: defeater of death aspect of Narasimha

Significance

Narasimha is a significant iconic symbol of creative resistance, hope against odds, victory over persecution, and destruction of evil. He is the destructor of not only external evil, but also one's own inner evil of "body, speech, and mind" states Pratapaditya Pal.[24].In South Indian art – sculptures, bronzes and paintings – Viṣṇu's incarnation as Narasiṃha is one of the most chosen themes and amongst Avatāras perhaps next only to Rāma and Kṛṣṇa in popularity. Lord Narasiṃha also appears as one of Hanuman's 5 faces,[25] who is a significant character in the Rāmāyaṇa as Lord (Rāma's) devotee.[citation needed]

Narasimha is worshipped across Telangana and Andhra Pradesh States in numerous forms.[26] Although, it is common that each of the temples contain depictions of Narasimha in more than one form, Ahobilam contains nine temples of Narasimha dedicated to the nine forms of Narasimha. It is also notable that the central aspect of Narasimha incarnation is killing the demon Hiranyakasipu, but that image of Narasimha is not commonly worshipped in temples, although it is depicted.

Coins, inscriptions and terracotta

The Narasimha legend was influential by the 5th-century, when various Gupta Empire kings minted coins with his images or sponsored inscriptions that associated the ethos of Narasimha with their own. The kings thus legitimized their rule as someone like Narasimha who fights evil and persecution.[27] Some of the coins of the Kushan era show Narasimha-like images, suggesting possible influence.[28]Some of the oldest Narasimha terracotta artworks have been dated to about the 2nd-century CE, such as those discovered in Kausambi.[29] A nearly complete, exquisitely carved standing Narasimha statue, wearing a pancha, with personified attributes near him has been found at the Mathura archeological site and is dated to the 6th-century.[30]

Performance arts

The Narasimha legends have been a part of various Indian classical dance repertoire. For example, Kathakali theatre has included the Narasimha-Hiranyakasipu battle storyline, and adaptations of Prahlada Caritam with Narasimha has been one of the popular performances in Kerala.[31] Similarly, the Bhagavata Mela dance-drama performance arts of Tamil Nadu traditionally celebrate the annual Narasimha jayanti festival by performing the story within regional Narasimha temples.[32]Prayers

A number of prayers have been written in dedication to Narasiṃha avatāra. These include:[citation needed]- The Narasiṃha Mahā-Mantra

- Narasiṃha Praṇāma Prayer

- Daśāvatāra Stotra by Jayadeva

- Kāmaśikha Aṣṭakam by Vedānta Deśika

- Divya Prabandham 2954

- Sri Lakshmi Narasimha Karavalamba Stotram

Early images

Narasiṃha statue

An image of Narasiṃha supposedly dating to second-third century AD sculpted at Mathura was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1987. It was described by Stella Kramrisch, the former Philadelphia Museum of Art's Indian curator, as "perhaps the earliest image of Narasiṃha as yet known".[35] This figure depicts a furled brow, fangs, and lolling tongue similar to later images of Narasiṃha, but the idol's robe, simplicity, and stance set it apart. On Narasiṃha's chest under his upper garment appears the suggestion of an amulet, which Stella Kramrisch associated with Visnu's cognizance, the Kauṣtubha jewel. This upper garment flows over both shoulders; but below Hiranyakasipu, the demon-figure placed horizontally across Narasiṃha's body, a twisted waist-band suggests a separate garment covering the legs. The demon's hair streams behind him, cushioning his head against the man-lion's right knee. He wears a simple single strand of beads. His body seems relaxed, even pliant. His face is calm, with a slight suggestion of a smile. His eyes stare adoringly up at the face of Viṣṇu. There is little tension in this figure's legs or feet, even as Narasiṃha gently disembowels him. His innards spill along his right side. As the Matsya purana describes it, Narasiṃha ripped "apart the mighty Daitya chief as a plaiter of straw mats shreds his reeds".[35] Based on the Gandhara-style of robe worn by the idol, Michael Meiste altered the date of the image to fourth century AD.[35]

An image of Narasiṃha, dating to the 9th century, was found on the northern slope of Mount Ijo, at Prambanan, Indonesia.[36] Images of Trivikrama and Varāha avatāras were also found at Prambanan, Indonesia. Viṣṇu and His avatāra images follow iconographic peculiarities characteristic of the art of central Java. This includes physiognomy of central Java, an exaggerated volume of garment, and some elaboration of the jewelry. This decorative scheme once formulated became, with very little modification, an accepted norm for sculptures throughout the Central Javanese period (circa 730–930 A.D.). Despite the iconographic peculiarities, the stylistic antecedents of the Java sculptures can be traced back to Indian carvings as the Chalukya and Pallava images of the 6th–7th centuries AD.[37]