The Rigveda (Sanskrit: ऋग्वेद ṛgveda, from ṛc "praise, shine" and veda "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns. It is one of the four canonical sacred texts (śruti) of Hinduism known as the Vedas. The text is a collection of 1,028 hymns and 10,600 verses, organized into ten books (Mandalas). A good deal of the language is still obscure and many hymns as a consequence are unintelligible.

The hymns are dedicated to Rigvedic deities. For each deity series the hymns progress from longer to shorter ones; and the number of hymns per book increases. In the eight books that were composed the earliest, the hymns predominantly discuss cosmology and praise deities. Books 1 and 10, which were added last, deal with philosophical or speculative questions about the origin of the universe and the nature of god, the virtue of dāna (charity) in society, and other metaphysical issues in its hymns.

Rigveda is one of the oldest extant texts in any Indo-European language. Philological and linguistic evidence indicate that the Rigveda was composed in the north-western region of the Indian subcontinent, most likely between c. 1500 and 1200 BC—though a wider approximation of c. 1700–1100 BC has also been given. The initial codification of the Rigveda took place during the early Kuru kingdom (c. 1200 – c. 900 BCE).

Some of its verses continue to be recited during Hindu rites of passage celebrations such as weddings and religious prayers, making it probably the world's oldest religious text in continued use.

Mandala

The text is organized in 10 books, known as Mandalas, of varying age and length.The "family books", mandalas 2–7, are the oldest part of the Rigveda and the shortest books; they are arranged by length (decreasing length of hymns per book) and account for 38% of the text. Within each book, the hymns are arranged in collections each dealing with a particular deity: Agni comes first, Indra comes second, and so on. They are attributed and dedicated to a rishi (sage) and his family of students. Within each collection, the hymns are arranged in descending order of the number of stanzas per hymn. If two hymns in the same collection have equal numbers of stanzas then they are arranged so that the number of syllables in the metre are in descending order.The second to seventh mandalas have a uniform format.

The eighth and ninth mandalas, comprising hymns of mixed age, account for 15% and 9%, respectively. The first and the tenth mandalas are the youngest; they are also the longest books, of 191 suktas each, accounting for 37% of the text. However, adds Witzel, some hymns in Mandala 8, 1 and 10 may be as old as the earlier Mandalas.[31] The first mandala has a unique arrangement not found in the other nine mandalas. The ninth mandala is arranged by both its prosody (chanda) structure and hymn length, while the first eighty four hymns of the tenth mandala have a structure different than the remaining hymns in it.

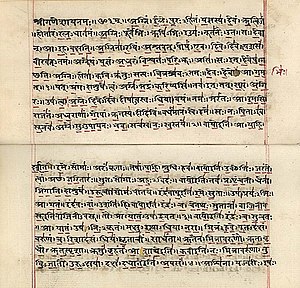

Rigveda (padapatha) manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century. After a scribal benediction ("śrīgaṇéśāyanamaḥ ;; Aum(3) ;;"), the first line has the opening words of RV.1.1.1 (agniṃ ; iḷe ; puraḥ-hitaṃ ; yajñasya ; devaṃ ; ṛtvijaṃ). The Vedic accent is marked by underscores and vertical overscores in red.

The surviving form of the Rigveda is based on an early Iron Age collection that established the core 'family books' (mandalas 2–7, ordered by author, deity and meter and a later redaction, co-eval with the redaction of the other Vedas, dating several centuries after the hymns were composed. This redaction also included some additions (contradicting the strict ordering scheme) and orthoepic changes to the Vedic Sanskrit such as the regularization of sandhi (termed orthoepische Diaskeuase by Oldenberg, 1888).

As with the other Vedas, the redacted text has been handed down in several versions, most importantly the Padapatha, in which each word is isolated in pausa form and is used for just one way of memorization; and the Samhitapatha, which combines words according to the rules of sandhi (the process being described in the Pratisakhya) and is the memorized text used for recitation.

The Padapatha and the Pratisakhya anchor the text's true meaning, and the fixed text was preserved with unparalleled fidelity for more than a millennium by oral tradition alone. In order to achieve this the oral tradition prescribed very structured enunciation, involving breaking down the Sanskrit compounds into stems and inflections, as well as certain permutations. This interplay with sounds gave rise to a scholarly tradition of morphology and phonetics. The Rigveda was probably not written down until the Gupta period (4th to 6th centuries AD), by which time the Brahmi script had become widespread (the oldest surviving manuscripts are from ~1040 AD, discovered in Nepal). The oral tradition still continued into recent times.

Recensions

Several shakhas ("branches", i. e. recensions) of Rig Veda are known to have existed in the past. Of these, Śākalya is the only one to have survived in its entirety. Another shakha that may have survived is the Bāṣkala, although this is uncertain.

The surviving padapatha version of the Rigveda text is ascribed to Śākalya. The Śākala recension has 1,017 regular hymns, and an appendix of 11 vālakhilya hymns which are now customarily included in the 8th mandala (as 8.49–8.59), for a total of 1028 hymns. The Bāṣkala recension includes 8 of these vālakhilya hymns among its regular hymns, making a total of 1025 regular hymns for this śākhā.In addition, the Bāṣkala recension has its own appendix of 98 hymns, the Khilani.

In the 1877 edition of Aufrecht, the 1028 hymns of the Rigveda contain a total of 10,552 ṛcs, or 39,831 padas. The Shatapatha Brahmana gives the number of syllables to be 432,000, while the metrical text of van Nooten and Holland (1994) has a total of 395,563 syllables (or an average of 9.93 syllables per pada); counting the number of syllables is not straightforward because of issues with sandhi and the post-Rigvedic pronunciation of syllables like súvar as svàr.

Three other shakhas are mentioned in Caraṇavyuha, a pariśiṣṭa (supplement) of Yajurveda: Māṇḍukāyana, Aśvalāyana and Śaṅkhāyana. The Atharvaveda lists two more shakhas. The differences between all these shakhas are very minor, limited to varying order of content and inclusion (or non-inclusion) of a few verses. The following information is known about the shakhas other than Śākalya and Bāṣkala:

- Māṇḍukāyana: Perhaps the oldest of the Rigvedic shakhas.

- Aśvalāyana: Includes 212 verses, all of which are newer than the other Rigvedic hymns.

- Śaṅkhāyana: Very similar to Aśvalāyana

- Saisiriya: Mentioned in the Rigveda Pratisakhya. Very similar to Śākala, with a few additional verses; might have derived from or merged with it.

Manuscripts

Versions

There are, for example, 30 manuscripts of Rigveda at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, collected in the 19th century by Georg Bühler, Franz Kielhorn and others, originating from different parts of India, including Kashmir, Gujarat, the then Rajaputana, Central Provinces etc. They were transferred to Deccan College, Pune, in the late 19th century. They are in the Sharada and Devanagari scripts, written on birch bark and paper. The oldest of them is dated to 1464. The 30 manuscripts of Rigveda preserved at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune were added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2007.Of these 30 manuscripts, 9 contain the samhita text, 5 have the padapatha in addition. 13 contain Sayana's commentary. At least 5 manuscripts (MS. no. 1/A1879-80, 1/A1881-82, 331/1883-84 and 5/Viś I) have preserved the complete text of the Rigveda. MS no. 5/1875-76, written on birch bark in bold Sharada, was only in part used by Max Müller for his edition of the Rigveda with Sayana's commentary.

Müller used 24 manuscripts then available to him in Europe, while the Pune Edition used over five dozen manuscripts, but the editors of Pune Edition could not procure many manuscripts used by Müller and by the Bombay Edition, as well as from some other sources; hence the total number of extant manuscripts known then must surpass perhaps eighty at least.

Comparison

The various Rigveda manuscripts discovered so far show some differences. Broadly, the most studied Śākala recension has 1017 hymns, includes an appendix of eleven valakhīlya hymns which are often counted with the 8th mandala, for a total of 1,028 metrical hymns. The Bāṣakala version of Rigveda includes eight of these vālakhilya hymns among its regular hymns, making a total of 1025 hymns in the main text for this śākhā. The Bāṣakala text also has an appendix of 98 hymns, called the Khilani, bringing the total to 1,123 hymns. The manuscripts of Śākala recension of the Rigveda have about 10,600 verses, organized into ten Books (Mandalas). Books 2 through 7 are internally homogeneous in style, while Books 1, 8 and 10 are compilation of verses of internally different styles suggesting that these books are likely a collection of compositions by many authors.The first mandala is the largest, with 191 hymns and 2,006 verses, and it was added to the text after Books 2 through 9. The last, or the 10th Book, also has 191 hymns but 1,754 verses, making it the second largest. The language analytics suggest the 10th Book, chronologically, was composed and added last. The content of the 10th Book also suggest that the authors knew and relied on the contents of the first nine books.

The Rigveda is the largest of the four Vedas, and many of its verses appear in the other Vedas.[56] Almost all of the 1,875 verses found in Samaveda are taken from different parts of the Rigveda, either once or as repetition, and rewritten in a chant song form. The Books 8 and 9 of the Rigveda are by far the largest source of verses for Sama Veda. The Book 10 contributes the largest number of the 1,350 verses of Rigveda found in Atharvaveda, or about one fifth of the 5,987 verses in the Atharvaveda text. A bulk of 1,875 ritual-focussed verses of Yajurveda, in its numerous versions, also borrow and build upon the foundation of verses in Rigveda .

Hymns

Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn of non-Eternity, origin of universe):

There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

Neither the realm of space, nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?

There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That One breathed, windless, by its own impulse;

Other than that there was nothing beyond.

Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That One by force of heat came into being;

Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

Gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?

Whether God's will created it, or whether He was mute;

Perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not;

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

Only He knows, or perhaps He does not know.

Neither the realm of space, nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?

There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That One breathed, windless, by its own impulse;

Other than that there was nothing beyond.

Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That One by force of heat came into being;

Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

Gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?

Whether God's will created it, or whether He was mute;

Perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not;

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

Only He knows, or perhaps He does not know.

The hymns mention various further minor gods, persons, phenomena and items, and contain fragmentary references to possible historical events, notably the struggle between the early Vedic people (known as Vedic Aryans, a subgroup of the Indo-Aryans) and their enemies, the Dasa or Dasyu and their mythical prototypes, the Paṇi (the Bactrian Parna).

- Mandala 1 comprises 191 hymns. Hymn 1.1 is addressed to Agni, and his name is the first word of the Rigveda. The remaining hymns are mainly addressed to Agni and Indra, as well as Varuna, Mitra, the Ashvins, the Maruts, Usas, Surya, Rbhus, Rudra, Vayu, Brhaspati, Visnu, Heaven and Earth, and all the Gods. This Mandala is dated to have been added to Rigveda after Mandala 2 through 9, and includes the philosophical Riddle Hymn 1.164, which inspires chapters in later Upanishads such as the Mundaka.[9][59][60]

- Mandala 2 comprises 43 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra. It is chiefly attributed to the Rishi gṛtsamada śaunahotra.

- Mandala 3 comprises 62 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra and the Vishvedevas. The verse 3.62.10 has great importance in Hinduism as the Gayatri Mantra. Most hymns in this book are attributed to viśvāmitra gāthinaḥ.

- Mandala 4 comprises 58 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra as well as the Rbhus, Ashvins, Brhaspati, Vayu, Usas, etc. Most hymns in this book are attributed to vāmadeva gautama.

- Mandala 5 comprises 87 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra, the Visvedevas ("all the gods'), the Maruts, the twin-deity Mitra-Varuna and the Asvins. Two hymns each are dedicated to Ushas (the dawn) and to Savitr. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the atri clan.

- Mandala 6 comprises 75 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra, all the gods, Pusan, Ashvin, Usas, etc. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the bārhaspatya family of Angirasas.

- Mandala 7 comprises 104 hymns, to Agni, Indra, the Visvadevas, the Maruts, Mitra-Varuna, the Asvins, Ushas, Indra-Varuna, Varuna, Vayu (the wind), two each to Sarasvati (ancient river/goddess of learning) and Vishnu, and to others. Most hymns in this book are attributed to vasiṣṭha maitravaruṇi.

- Mandala 8 comprises 103 hymns to various gods. Hymns 8.49 to 8.59 are the apocryphal vālakhilya. Hymns 1–48 and 60–66 are attributed to the kāṇva clan, the rest to other (Angirasa) poets.

- Mandala 9 comprises 114 hymns, entirely devoted to Soma Pavamana, the cleansing of the sacred potion of the Vedic religion.

- Mandala 10 comprises additional 191 hymns, frequently in later language, addressed to Agni, Indra and various other deities. It contains the Nadistuti sukta which is in praise of rivers and is important for the reconstruction of the geography of the Vedic civilization and the Purusha sukta which has been important in studies of Vedic sociology.[61] It also contains the Nasadiya sukta (10.129), probably the most celebrated hymn in the west, which deals with creation.[10] The marriage hymns (10.85) and the death hymns (10.10–18) still are of great importance in the performance of the corresponding Grhya rituals.

Rigveda

Brahmanas

The Kaushitaka is, upon the whole, far more concise in its style and more systematic in its arrangement features which would lead one to infer that it is probably the more modern work of the two. It consists of thirty chapters (adhyaya); while the Aitareya has forty, divided into eight books (or pentads, pancaka), of five chapters each. The last ten adhyayas of the latter work are, however, clearly a later addition though they must have already formed part of it at the time of Pāṇini (c. 5th century BC), if, as seems probable, one of his grammatical sutras, regulating the formation of the names of Brahmanas, consisting of thirty and forty adhyayas, refers to these two works. In this last portion occurs the well-known legend (also found in the Shankhayana-sutra, but not in the Kaushitaki-brahmana) of Shunahshepa, whom his father Ajigarta sells and offers to slay, the recital of which formed part of the inauguration of kings.

While the Aitareya deals almost exclusively with the Soma sacrifice, the Kaushitaka, in its first six chapters, treats of the several kinds of haviryajna, or offerings of rice, milk, ghee, etc., whereupon follows the Soma sacrifice in this way, that chapters 7–10 contain the practical ceremonial and 11–30 the recitations (shastra) of the hotar. Sayana, in the introduction to his commentary on the work, ascribes the Aitareya to the sage Mahidasa Aitareya (i.e. son of Itara), also mentioned elsewhere as a philosopher; and it seems likely enough that this person arranged the Brahmana and founded the school of the Aitareyins. Regarding the authorship of the sister work we have no information, except that the opinion of the sage Kaushitaki is frequently referred to in it as authoritative, and generally in opposition to the Paingya—the Brahmana, it would seem, of a rival school, the Paingins. Probably, therefore, it is just what one of the manuscripts calls it—the Brahmana of Sankhayana (composed) in accordance with the views of Kaushitaki.

Rigveda Aranyakas and Upanishads

Each of these two Brahmanas is supplemented by a "forest book", or Aranyaka. The Aitareyaranyaka is not a uniform production. It consists of five books (aranyaka), three of which, the first and the last two, are of a liturgical nature, treating of the ceremony called mahavrata, or great vow. The last of these books, composed in sutra form, is, however, doubtless of later origin, and is, indeed, ascribed by Hindu authorities either to Shaunaka or to Ashvalayana. The second and third books, on the other hand, are purely speculative, and are also styled the Bahvrca-brahmana-upanishad. Again, the last four chapters of the second book are usually singled out as the Aitareya Upanishad,[63] ascribed, like its Brahmana (and the first book), to Mahidasa Aitareya; and the third book is also referred to as the Samhita-upanishad. As regards the Kaushitaki-aranyaka, this work consists of 15 adhyayas, the first two (treating of the mahavrata ceremony) and the 7th and 8th of which correspond to the 1st, 5th, and 3rd books of the Aitareyaranyaka, respectively, whilst the four adhyayas usually inserted between them constitute the highly interesting Kaushitaki (Brahmana-) Upanishad, of which we possess two different recensions. The remaining portions (9–15) of the Aranyaka treat of the vital airs, the internal Agnihotra, etc., ending with the vamsha, or succession of teachers.Composition

The earliest text were composed in greater Punjab (northwest India and Pakistan), and the more philosophical later texts were most likely composed in or around the region that is the modern era state of Haryana.Philological estimates tend to date the bulk of the text to the second half of the second millennium.[n

Being composed in an early Indo-Aryan language, the hymns must post-date the Indo-Iranian separation, dated to roughly 2000 BC. A reasonable date close to that of the composition of the core of the Rigveda is that of the Mitanni documents of c. 1400 BC, which contain Indo-Aryan nomenclature. Other evidence also points to a composition close to 1400 BC.

The Rigveda's core is accepted to date to the late Bronze Age, making it one of the few examples with an unbroken tradition. Its composition is usually dated to roughly between c. 1500–1200 BC.

Codification

There is a widely accepted timeframe for the initial codification of the Rigveda by compiling the hymns very late in the Rigvedic or rather in the early post-Rigvedic period, including the arrangement of the individual hymns in ten books, coeval with the composition of the younger Veda Samhitas.[citation needed] This time coincides with the early Kuru kingdom, shifting the center of Vedic culture east from the Punjab into what is now Uttar Pradesh. The fixing of the samhitapatha (by keeping Sandhi) intact and of the padapatha (by dissolving Sandhi out of the earlier metrical text), occurred during the later Brahmana period.Composition

The earliest text were composed in greater Punjab (northwest India and Pakistan), and the more philosophical later texts were most likely composed in or around the region that is the modern era state of Haryana.Philological estimates tend to date the bulk of the text to the second half of the second millennium.[n

Being composed in an early Indo-Aryan language, the hymns must post-date the Indo-Iranian separation, dated to roughly 2000 BC. A reasonable date close to that of the composition of the core of the Rigveda is that of the Mitanni documents of c. 1400 BC, which contain Indo-Aryan nomenclature. Other evidence also points to a composition close to 1400 BC.

The Rigveda's core is accepted to date to the late Bronze Age, making it one of the few examples with an unbroken tradition. Its composition is usually dated to roughly between c. 1500–1200 BC.

Codification

There is a widely accepted timeframe for the initial codification of the Rigveda by compiling the hymns very late in the Rigvedic or rather in the early post-Rigvedic period, including the arrangement of the individual hymns in ten books, coeval with the composition of the younger Veda Samhitas.[citation needed] This time coincides with the early Kuru kingdom, shifting the center of Vedic culture east from the Punjab into what is now Uttar Pradesh. The fixing of the samhitapatha (by keeping Sandhi) intact and of the padapatha (by dissolving Sandhi out of the earlier metrical text), occurred during the later Brahmana period.Contemporary Hinduism

He who studies understands,

not the one who sleeps.

not the one who sleeps.

The social history and context of the Vedic texts are extremely distant from contemporary Hindu religious beliefs and practice, a reverence for the Vedas as an exemplar of Hindu heritage continues to inform a contemporary understanding of Hinduism. Popular reverence for Vedic scripture is similarly focused on the abiding authority and prestige of the Vedas rather than on any particular exegesis or engagement with the subject matter of the text.

— Andrea Pinkney, Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia

"Indigenous Aryans" debate

Alternative theory for a much earlier composition date for the Rigveda, as well as the Indigenous Aryans theory have been suggested. These theories are controversial.Translations

Mistranslations, misinterpretations debate

The Rig Veda is hard to translate accurately, because it is the oldest Indo-Aryan text, composed in the archaic Vedic Sanskrit. There are no closely contemporary extant texts, which makes it difficult to interpret.Early missionaries and colonial administrators in India, used Western concepts and words in their attempts to translate and interpret the ancient texts of Indian religions. This, state postmodern scholars such as Frits Staal, led to mistranslations. Thus, Rigveda's Mandala are often translated to mean 'Book', when the word actually means 'Cycle', according to Staal. The Vedas were called 'sacred books', an appellation borrowed by orientalists used for Bible, but there is no evidence of this. Staal states, "it is nowhere stated that the Veda was revealed", and Sruti simply means "that what is heard, in the sense that it is transmitted from father to son or from teacher to pupil". The Rigveda, or other Vedas, do not anywhere assert that they are Apauruṣeyā, and this reverential term appears centuries later in the texts of the Mimamsa school of Hindu philosophy.[110][112] The text of Rigveda suggests it was "composed by poets, human individuals whose names were household words" in the Vedic age, states Staal.

The Rigveda is the earliest, the most venerable, obscure, distant and difficult for moderns to understand – hence is often misinterpreted or worse: used as a peg on which to hang an idea or a theory.

— Frits Staal, Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights[114]

Translations

The first published translation of any portion of the Rigveda in any European language was into Latin, by Friedrich August Rosen (Rigvedae specimen, London 1830). Predating Müller's editio princeps of the text by 19 years, Rosen was working from manuscripts brought back from India by Colebrooke. H. H. Wilson was the first to make a complete translation of the Rig Veda into English, published in six volumes during the period 1850–88. Wilson's version was based on the commentary of Sāyaṇa. Müller's Rig Veda Sanhita in 6 volumes Muller, Max, ed. (W. H. Allen and Co., London, 1849) has an English preface The birch bark from which Müller produced his translation is held at The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, India.Some notable translations of the Rig Veda include:

| Title | Translator | Year | Language | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigvedae specimen | Friedrich August Rosen | 1830 | Latin | Partial translation with 121 hymns (London, 1830). Also known as Rigveda Sanhita, Liber Primus, Sanskrite Et Latine (ISBN 978-1275453234). Based on manuscripts brought back from India by Henry Thomas Colebrooke. |

| Rig-Veda, oder die heiligen Lieder der Brahmanen | Max Müller | 1856 | German | Partial translation published by F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig. In 1873, Müller published an editio princeps titled The Hymns of the Rig-Veda in the Samhita Text. He also translated a few hymns in English (Nasadiya Sukta). |

| Ṛig-Veda-Sanhitā: A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns | H. H. Wilson | 1850-88 | English | Published as 6 volumes, by N. Trübner & Co., London. |

| Rig-véda, ou livre des hymnes | A. Langlois | 1870 | French | Partial translation. Re-printed in Paris, 1948–51 (ISBN 2-7200-1029-4). |

| Der Rigveda | Alfred Ludwig | 1876 | German | Published by Verlag von F. Tempsky, Prague. |

| Rig-Veda | Hermann Grassmann | 1876 | German | Published by F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig |

| Rigved Bhashyam | Dayananda Saraswati | 1877-9 | Hindi | Incomplete translation. Later translated into English by Dharma Deva Vidya Martanda (1974). |

| The Hymns of the Rig Veda | Ralph T.H. Griffith | 1889-92 | English | Revised as The Rig Veda in 1896. Revised by JL Shastri in 1973. |

| Der Rigveda in Auswahl | Karl Friedrich Geldner | 1907 | German | Published by W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart. Geldner's 1907 work was a partial translation; he completed a full translation in the 1920s, which was published after his death, in 1951.[118] This translation was titled Der Rig-Veda: aus dem Sanskrit ins Deutsche Übersetzt. Harvard Oriental Studies, vols. 33–37 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1951-7). Reprinted by Harvard University Press (2003) ISBN 0-674-01226-7. |

| Hymns from the Rigveda | A. A. Macdonell | 1917 | English | Partial translation (30 hymns). Published by Clarendon Press, Oxford. |

| Series of articles in Journal of the University of Bombay | Hari Damodar Velankar | 1940s-1960s | English | Partial translation (Mandala 2, 5, 7 and 8). Later published as independent volumes. |

| Rig Veda - Hymns to the Mystic Fire | Sri Aurobindo | 1946 | English | Partial translation published by NK Gupta, Pondicherry. Later republished several times (ISBN 9780914955221) |

| Rig Veda | Ramgovind Trivedi | 1954 | Hindi | |

| Études védiques et pāṇinéennes | Louis Renou | 1955-69 | French | Appears in a series of publications, organized by the deities. Covers most of Rigveda, but leaves out significant hymns, including the ones dedicated to Indra and the Asvins. |

| ऋग्वेद संहिता | Shriram Sharma | 1950s | Hindi | |

| Hymns from the Rig-Veda | Naoshiro Tsuji | 1970 | Japanese | Partial translation |

| Rigveda: Izbrannye Gimny | Tatyana Elizarenkova | 1972 | Russian | Partial translation, extended to a full translation published during 1989–1999. |

| Rigveda Parichaya | Nag Sharan Singh | 1977 | English / Hindi | Extension of Wilson's translation. Republished by Nag, Delhi in 1990 (ISBN 978-8170812173). |

| Rig Veda | M. R. Jambunathan | 1978-80. | Tamil | Two volumes, both released posthumously. |

| Rigvéda – Teremtéshimnuszok (Creation Hymns of the Rig-Veda) | Laszlo Forizs (hu) | 1995 | Hungarian | Partial translation published in Budapest (ISBN 963-85349-1-5) |

| The Rig Veda | Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty | 1981 | English | Partial translation (108 hymns), along with critical apparatus. Published by Penguin (ISBN 0-14-044989-2). A bibliography of translations of the Rig Veda appears as an Appendix. |

| Pinnacles of India's Past: Selections from the Rgveda | Walter H. Maurer | 1986 | English | Partial translation published by John Benjamins. |

| The Rig Veda | Bibek Debroy, Dipavali Debroy | 1992 | English | Partial translation published by B. R. Publishing (ISBN 9780836427783). The work is in verse form, without reference to the original hymns or mandalas. Part of Great Epics of India: Veda series, also published as The Holy Vedas. |

| The Holy Vedas: A Golden Treasury | Pandit Satyakam Vidyalankar | 1983 | English | |

| Ṛgveda Saṃhitā | HH Wilson, Ravi Prakash Arya and K. L. Joshi | 2001 | English | 4-volume set published by Parimal (ISBN 978-81-7110-138-2). Revised edition of Wilson's translation. Replaces obsolete English forms with more modern equivalents (e.g. "thou" with "you"). Includes the original Sanskrit text in Devanagari script, along with a cristical apparatus. |

| Ṛgveda for the Layman | Shyam Ghosh | 2002 | English | Partial translation (100 hymns). Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. |

| Rig-Veda | Michael Witzel, Toshifumi Goto | 2007 | German | Partial translation (Mandala 1 and 2). The authors are working on a second volume. Published by Verlag der Weltreligionen (ISBN 978-3-458-70001-2). |

| ऋग्वेद | Govind Chandra Pande | 2008 | Hindi | Partial translation (Mandala 3 and 5). Published by Lokbharti, Allahabad |

| The Hymns of Rig Veda | Tulsi Ram | 2013 | English | Published by Vijaykumar Govindram Hasanand, Delhi |

| The Rigveda | Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton | 2014 | English | 3-volume set published by Oxford University Press (ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4). Funded by the United States' National Endowment for the Humanities in 2004.[119] |

SOURCES : WIKIPEDIA AND RIG VEDA

POSTED BY : VIPUL KOUL

EDITED BY : ASHOK KOUL

Very informative and interesting.

ReplyDeleteCongratulations! Indeed praiseworthy. Just to add as the Rgveda itself mentions that agni, indra, aditya,surya, etc. refer to the one Supreme being. Therefore, all the mantras praise the one God using different names.

ReplyDelete